Hello readers and welcome to our group read of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn!

Wrapped in a YA story, it would be easy to see the attitude and rebellion of Twain’s characters as little more than youthful defiance. But reading the likes of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn as an adult creates a richer, deeper perspective. We see the hypocrisy that often comes with adulthood, we see the simple wisdom that only children can give, and we see the whimsy and bravery that tend to wane along with our teenage and twentysomething years.

Twain’s most famous works are often found in children’s sections at bookstores and libraries, but they can also profoundly speak to the adult experience.

As we jump into Huck Finn this week, I wanted to provide just a bit of context and background for the story.

Note: All quotes in the first section are from Ron Chernow’s upcoming Mark Twain. Publishing in mid-May, it makes for a fantastic companion to Huck Finn.

Finally, here’s the reading schedule once again if needed.

Samuel Clemens & Mark Twain: Midwestern Boy at Heart

“The search for untrammeled truth and freedom would form a defining quest of Mark Twain’s life.”

As an adult man whose best-known characters were teenage boys, it doesn’t take intense literary analysis to infer that Mark Twain had a romantic and nostalgic view of youth. Born as Samuel Clemens in 1835, he craved attention and celebrity from a young age and went on to attain exactly that, beyond even his wildest dreams. In fact, Ron Chernow posits that:

“Mark Twain fairly invented our celebrity culture, seemingly anticipating today’s world of social analysts and influencers.”

As that fame grew, though, he yearned for the innocence of his childhood, most fondly spent as countless carefree hours rambling along the Mississippi River in northeastern Missouri.

“Like Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, Sam exhibited an outlaw spirit, preferring to tarry on the fringes of town . . . most of all on the river with its mysterious, isolated islands, where he gloried in a sense of freedom.”

He was a rebellious, trouble-making boy himself, just as Sawyer and Finn, and came to despise the hypocrisy that so often came with adulthood:

“This fascination with marginal and taboo figures prefigures the radical vision of Twain’s fiction in which he found virtue in the low born, vice in the well bred, lending a dark glamour to boys flouted parental strictures.”

And it’s worth nothing that the humor found in his narratives is not just playful:

“The sources of his humor are deadly serious, rooted in a profound critique of society and human nature that gives his jokes their staying power.”

In all his writing, but especially Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, Twain was trying both to capture a foregone time as well as make a clear point about what actually matters in life and what doesn’t.

Huck Finn: An Adventurous Outcast

While the character of Huck Finn shows up in Tom Sawyer, it’s not strictly necessary to read the two books together. That said, Tom Sawyer does provide some interesting backdrop and context for the character of Huck Finn.

When Huck was first introduced in Tom Sawyer, Twain provided readers with some helpful description:

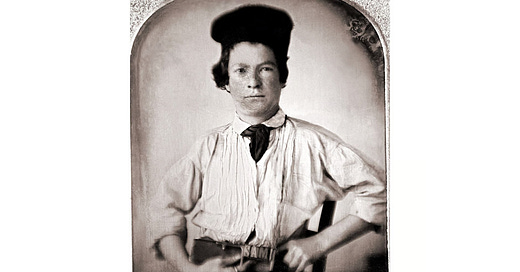

“the juvenile pariah of the village, Huckleberry Finn, son of the town drunkard. Huckleberry was cordially hated and dreaded by all the mothers of the town, because he was idle and lawless and vulgar and bad—and because all their children admired him so, and delighted in his forbidden society, and wished they dared to be like him.”

He’s an outcast. He’s on the edges. He doesn’t have a family life. Other parents hate him, but their kids love him. In this light, you’d perhaps even call him a rebel. But later in Tom Sawyer we got another description which paints a sadder picture:

“Huckleberry came and went, at his own free will. He slept on doorsteps in fine weather and in empty hogsheads in wet; he did not have to go to school or to church, or call any being master or obey anybody; he could go fishing or swimming when and where he chose, and stay as long as it suited him; nobody forbade him to fight; he could sit up as late as he pleased; he was always the first boy that went barefoot in the spring and the last to resume leather in the fall; he never had to wash, nor put on clean clothes; he could swear wonderfully. In a word, everything that goes to make life precious, that boy had.”

Twain’s tone is actually a bit romantic here, but as a parent, I just felt sad for Huck. He had nobody looking after him. Regardless of Twain’s intent, this framing is certain to color my understand of Huck.

One final thing worth noting is the significance of the name Huckleberry itself. A scholarly article from 1971 posits that the qualities of the berry itself go a long way towards explaining Twain’s choice:

“An American word, ‘huckleberry’ originated about 1670 and appeared in some common expressions with connotations of insignificance and rusticity, both qualities appropriate for Huck. . . . The appropriateness of huckleberry is underlined by a quality of the berry itself. As Thoreau and others tell us, it does not submit to cultivation and tastes best when picked wild. Twain's Huckleberry, too, resisted domestication.”

Again, what appears to be a simple children’s story is much more layered once slow down and explore what’s just beneath the surface.

Thanks for reading along with me. I can’t wait to dig in.

-Jeremy

Jeremy, I share your dismay at Huck's unmoored life and his casual acceptance of physical abuse, although I don't identify with his "civilizing" aunt, either.

Is anyone else stopped cold by the n-word? I'm not at all arguing that it should be censored, but it's amazing that six letters in a particular sequence can carry such an emotional charge.

Wow. Thanks. These notes and the video were very informative.